Note: The publication copyright of this article belongs to Pergas. No part of this article may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise without the permission of Pergas. Permission is only given for sharing this article via its original URL.

Opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not represent Pergas’ official stand unless if Pergas explicitly says so.

———————————

Contradicting Wasatiyah: Are Theological Differences the Main Reason of Sectarianism?

By Syed Huzaifah Bin Othman Alkaff

Introduction

Introduction

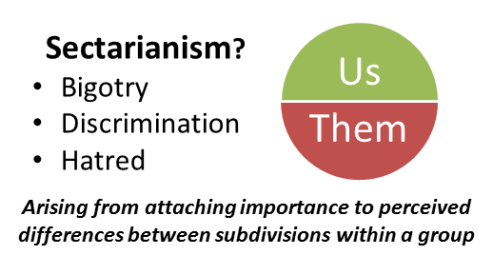

One of the issues concerning wasatiyah today concerns the increased tendency towards sectarianism among Muslims and one of the main factors that fuels this abhorrent tendency is the on-going conflict and political development in the Middle East. Most pervasive manifestations of sectarianism in neighbouring countries are in the form of hate speech exchanged between rivalling sects. However, extreme forms such the pronouncement of takfir (excommunication) and even violence do occur.

Although Singapore Muslim community has been saved thus far from violent sectarian conflict, there are signs to indicate that the less serious ones are making way into theological discourses along the line of Sunni-Shiite and Ahl Al-Sunnah Wa Al-Jamaah-Salafi/Wahabi divide. This must be addressed before it gets worst, at least, for two main reasons; a) sectarianism is in conflict with wasatiyah – the key feature of Islam (theological reason), and b) sectarianism is detrimental to harmonious intra-faith relations which may have serious implications too on the larger Singapore community.

Often theological differences are pointed out as the main culprit to sectarianism. This is particularly so when looking at the current conflict in the Middle East where Sunni-Shiite theological differences is highlighted as the reason. Not denying the role of theological differences, this article seeks to highlight that the more important reason to violent clashes between Sunnis and Shiites in the region is the politicisation of theological divide for power politics i.e. regional hegemony and local political authority. Thus, local Muslim here must not be quick to fault theological differences and allow these over hundred years of unresolved differences to evolve into sectarianism. The current conflict should not be allowed to erase the fact that, over the history, Muslims from different sects had and can live together harmoniously.

Sectarianism has been plaguing the political struggles of the Middle East. Sectarian differences within the Muslim world are not a recent phenomenon. However, the Middle East region in particular is witnessing proliferation of sectarian rhetoric since the invasion of Iraq by the US and its allies in 2003.

There are acknowledged differences in the juridical (fiqh) aspect within the religion itself, and these have become part of the Islamic schools of thought (mazhab). Yet, there have been significant religious doctrines that have been shaped by political conflicts rather than religious and academic scholarship. It is these types of doctrines that have given a detrimental dimension to the differences within the religion itself. These doctrines, which were previously only argumentative standpoints in religious discourse, have been incorporated into mainstream Islamic theology. They have incidentally been set as the foundations for Islamist activism to build an ideology that mobilises its followers into espousing exclusivist ideas.

Political conflicts shaping religious doctrines

A historical demonstration of this notion is the split of Islam into its two main sects – Sunni and Shiite. The split between the Sunni and Shiite can be traced back to the fundamental debate on the selection of a rightful successor after the Prophet Muhammad. The Shiites believed that the leadership should stay within the family of the Prophet, while the Sunnis believed leadership is not limited to the family of the Prophet. The leadership struggle worsened after the death of `Ali bin Abi Talib, the cousin of the Prophet (the fourth Caliph), resulting in violence and war. Since then, wars between the two sects will always have sectarian undertones. Although the initial reason for the split was struggle for political leadership, the Sunni and Shiite differences now stem deep into competing belief systems regarding religious leadership, theology, jurisprudence, ways of worship and more.

Further heightening the religious split is the advent of Shiite political establishment – the Safavid dynasty in Persia, 1501. Shah Ismail the First declared Shi’ism to be the formal doctrine of the new state to distinguish his new state from the Sunni Ottoman Empire. The position of the Safavids close to the Sunni Caliphate – the Ottomans – set the political, geographical and demographic distribution of the two sects (Rabie, 1978). As Shias have been rejecting the authority of Sunni rulers since the death of Ali, the political establishment of the Safavid dynasty further drew the lines between the two as it presented a stronger and consolidated challenge against the Sunni authority. Similarly, the 1979 Iranian Revolution reinforced the split by challenging the dominant Sunni political presence in the region.

Further heightening the religious split is the advent of Shiite political establishment – the Safavid dynasty in Persia, 1501. Shah Ismail the First declared Shi’ism to be the formal doctrine of the new state to distinguish his new state from the Sunni Ottoman Empire. The position of the Safavids close to the Sunni Caliphate – the Ottomans – set the political, geographical and demographic distribution of the two sects (Rabie, 1978). As Shias have been rejecting the authority of Sunni rulers since the death of Ali, the political establishment of the Safavid dynasty further drew the lines between the two as it presented a stronger and consolidated challenge against the Sunni authority. Similarly, the 1979 Iranian Revolution reinforced the split by challenging the dominant Sunni political presence in the region.

Another example of doctrinal debate within Islam is one within the Sunni sect itself. Seceders (Kharijite) and Postponers (Murji’ah) are two main doctrines that began as religious arguments revolving around the issue of religious judgment.

One argument pertains to the term irja’ or Murji’ah which means ‘postponement’ and refers to the belief that only God holds the authority to judge one’s faith and actions. Therefore, a Muslim remains a Muslim so long as they are faithful to the shahadah (Islamic Testimony of Faith). In other words, humans are not in any way qualified to judge one’s actions or beliefs. This term arose from the political conflict during the time between the third caliph, `Uthman bin `Affan and his successor `Ali. Those who took the position of Murji’ah believed in not taking any sides or passing any judgements, and instead advocated postponing the judgement of the matter to God. On the other hand, the Kharijite holds the opposite view which applies Qur’anic rulings so strictly that they advocated excommunicating Muslims found guilty of major sins and they would justify taking up arms against them (Black, 2011). These argumentative positions also became religious doctrines.

Today, the ideological manifestation of Kharijite appears in the Jihadist conception of jihad where fighting is deemed legitimate and mandatory against rulers (Muslims and non-Muslims) who do not implement Islamic law.

Political conflicts shaping dynamics in Islamic society

The current sectarian turmoil affects the dynamics of the Muslim world especially on two particular levels. On the social level, the turmoil has forced the Sunni leaders in the Middle East to convene and actively discuss the consequences of it, namely religious extremism and terrorism, with unintended consequences, however.

One of these efforts was the Grozny conference, on 25th to 27th August 2016, which sought to define the ‘true’ identity of a Sunni Muslim, more commonly termed as “Ahl Al-Sunnah Wa Al-Jamaah” (Kadhim, 2016). In the Southeast Asian region, ASWAJA is the recognised acronym that refers to the ‘true Sunni identity’ idea. The conference emphasised on the danger of the takfiri (excommunication) practices of Salafi-Jihadists and responded to the threat – ironically – by excluding them from the fold. Inadvertently, the conference intimidated certain sects within Salafism. As such, another conference was initiated in Kuwait on 12 November 2016 which sought to refine the definition of ASWAJA to include the other sects and groups that had been excluded as a result of the Grozny conference (Aljazeera.net, 2016).

These efforts at refining the ‘true’ identity of a Sunni Muslim mirrors the past trends of incrementally developing religious arguments or standpoints into a religious doctrine. These will undoubtedly have a definitive impact on shaping the Sunni community of the future. Hence, it is pertinent that caution mus t be observed in engaging in such practice as it can lead to another deep division within Islam. Alarmingly, there have been trends that show the increasing hegemonic inclinations of certain groups under the label of “Ahl Al-Sunnah Wa Al-Jamaah”. These groups have begun to engage in the act of vilifying other sects. This occurrence is a very strong manifestation of the current religious discourse defining a ‘true’ Muslim. The people on the ground have shown that they are responsive to and adoptive of the idea of strictly defining and becoming the ‘true’ Muslim. It sends a clear signal to religious scholars that their authoritative moves can directly affect the social dynamics on the ground.

t be observed in engaging in such practice as it can lead to another deep division within Islam. Alarmingly, there have been trends that show the increasing hegemonic inclinations of certain groups under the label of “Ahl Al-Sunnah Wa Al-Jamaah”. These groups have begun to engage in the act of vilifying other sects. This occurrence is a very strong manifestation of the current religious discourse defining a ‘true’ Muslim. The people on the ground have shown that they are responsive to and adoptive of the idea of strictly defining and becoming the ‘true’ Muslim. It sends a clear signal to religious scholars that their authoritative moves can directly affect the social dynamics on the ground.

On the political level, rifts among Middle Eastern countries continue to occur. The arguments between the countries are essentially political, although it may have religious undertones.

In the early June 2017, several Arab countries including Saudi Arabia and Egypt cut their diplomatic ties with Qatar over its alleged support for terrorism from Islamist groups (Wintour, 2017). A week later, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt published a list of 59 people and 12 entities that they have recognised as terrorist entities or have connections to terrorist entities (The National, 2017). It is worthy to highlight that this is not a new experience for Qatar. In March 2014, its relationships with the other members of the GCC worsened when Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and United Arab Emirates withdrew their ambassadors from Qatar. Qatari diplomatic isolation again has been affected by the same allegation of Qatari support for Islamist groups (BBC News, 2014).

Qatar and Saudi are of similar religious conservatism – Wahhabism – but that does not stop them from fighting over the religio-political. Saudi Arabia is often regarded as being the regional power for having presumably sacred geography, inflated Islamic credentials, massive oil wealth and charismatic patriarchs (Al-Rasheed, 2016). Qatar on the other hand, emphasises the importance of having good diplomacy and alliance in order to challenge Saudi as a regional power. This is demonstrated in Qatar’s involvement in mediation, conflict resolution and support at regional and international level, in several conflicts such as those taking place in Syria, Sudan, Somalia, Lebanon, Palestine and Libya. In addition, the Arab Spring in late 2010 led to the declining of traditional powers, particularly Egypt and Saudi Arabia. As a result, the power vacuum in the region compelled Qatar to take the leadership position in the region and forming alliances (Blasi, 2015).

The leadership position provides Qatar with an avenue to pursue for global recognition while establishing itself as a major player in the region. To achieve that, Qatar welcomed and supported the overthrow of authoritarian regimes in the Arab Spring. Qatar became the region’s key agent for diplomatic and logistic support of the revolutionary forces in Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen (Blasi, 2015). Qatar’s support for Islamist groups is very important to Qatar to reconfigure the balance of power in the region. Islamist groups in general and Muslim Brotherhood in particular are those who Qatar viewed as an opportunity to work with to achieve its political interest. Qatar also played an immense role in supporting countries in conflict, especially in political and financial terms. Qatar’s economic strength as the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) empowers Qatar to play these influential roles in the region.

For instance, Qatar’s presence was key in the Libyan conflict as Qatar continuously supported the UN-backed political dialogue. The support resulted in the signing of the Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) in Morocco in December 2015. As a result, the internationally recognised government, the Government of National Accord (GNA), was formed. Apart from giving political support in Libya, Qatar is also financially supporting  the Islamist militias, such as the Benghazi Defence Brigade (BDB). BDB is listed in the list of 59 people and 12 entities published by Saudi Arabia and its allies (El-Gamaty, 2017). BDB leaders such as Ismail Sallabi, a renowned Islamist activist and Afghan war veteran, have been given safe haven and also receiving arms from Qatar (Reuters, 2011).

the Islamist militias, such as the Benghazi Defence Brigade (BDB). BDB is listed in the list of 59 people and 12 entities published by Saudi Arabia and its allies (El-Gamaty, 2017). BDB leaders such as Ismail Sallabi, a renowned Islamist activist and Afghan war veteran, have been given safe haven and also receiving arms from Qatar (Reuters, 2011).

Similarly, Qatar is involved politically and financially in Syria. It was reported in 2013 that the country had spent at least $3 billion dollars supporting the opposition groups in Syria (Khalaf and Smith, 2013). For example, the Syrian National Council (SNC), which is Qatar’s brainchild, was formed with its financial and political support. Among others, Qatar also gave SNC an official seat during the Arab League Summit in 2013 (Moubayed, 2017). SNC was not the only group or Syrian opposition coalition force that Qatar supported, as there are also many other groups in Syria that Qatar funds. Qatar was also the first to call for an armed Arab Military Intervention in Syria after continuous atrocities committed by the Syrian government against protesters and calls for non-violence were ignored (Al-Thani, 2017).

While attempting to be a major political player in the region, Qatar is also using its soft power to play religious politics and influence the Islamist activism in the region. Qatar maintains a strong relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood and many other opposition movements in order to serve Qatar’s political interest in the region. Libya and Syria have not been successful ground for Qatar yet. But in Egypt, Qatar was able to form a Qatar-Egypt-Turkish axis during Morsi’s leadership in Egypt (Al-Thani, 2017). The alliance challenged Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Egypt as Egypt is Saudi’s closest ally. This shook Saudi as they were concerned if the Muslim Brotherhood would export the Arab Spring to Saudi Arabia or influence a change in Egypt’s policy towards Saudi Arabia.

Essentially, Middle-Eastern rifts have been very much political. The support for any religious (Islamist) groups is for the intention to having greater support and alliance to serve the political interests. Thus, the act of politicisation of religious groups and manipulation is proven to shape the dynamics of the Islamic society today.

Going Forward

Sectarian divisions are inevitable in any religious groups. However, it is the politicisation of religion in conflict that has a huge impact on the community. Nevertheless, it is also impossible to fully separate religion from politics. These three points are critical for religious elites in Singapore to be cognisant with when dealing with sectarian issue, be it between Sunni-Shiite, ASWAJA-Salafi or Sunni-Ahmadiyah. By having these points in mind, religious elites would be able to avoid simplistic view to fault theological differences and frame intra-faith tension or conflict as a theological problem.

Some suggestions can be offered here. Firstly, religious elites of various sects in Islam are to work on common grounds within Islam in contrast to the inefficient practice of drawing lines between sects and groups. One way is to give greater focus on the fundamentals of Islam as a religion, such as the preservation of the five principles (Maqasid Shari`ah); life, religion, intellect, progeny, and wealth. Secondly, the religious elites should lead by examples by not vilifying and denigrating others i.e. hate speech, dehumanisation of others, and quick to denounce such acts that appear from their congregation because these are the beginning of many religious conflicts all over the world.

————————————————-

References

- Al-Rasheed, M. (2016). Saudi Arabia and the quest for regional hegemony | Hurst Publishers. HURST. Available at: http://www.hurstpublishers.com/saudi-arabia-quest-regional-hegemony/ [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- Al-Thani, S. (2017). The Qatari-Saudi-Egyptian Triangle After the Arab Spring. In Mason R. (Ed.), Egypt and the Gulf: A Renewed Regional Policy Alliance, Germany: Gerlach Press, Berlin, pp. 62-77.

- net. (2016). Mu’tamar Islamiy Bi Al-Kuwait Yuakkid `Ala Wahdah Ahl Al-Sunnah. Available at: http://www.aljazeera.net/news/arabic/2016/11/12/%D9%85%D8%A4%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%B1-%D8%A5%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%83%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%AA-%D9%8A%D8%A4%D9%83%D8%AF-%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-%D9%88%D8%AD%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A3%D9%87%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%86%D8%A9 [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- BBC News. (2014). Gulf ambassadors pulled from Qatar over ‘interference’ – BBC News. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-26447914 [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- Black, A. (2011). The Mission of Muhammad. In The History of Islamic Political Thought: From the Prophet to the Present(pp. 15-17). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Blasi, F. (2015). Qatar’s foreign policy, the challenges in the MENA region. Mediterranean Affairs. Available at: http://mediterraneanaffairs.com/qatar-s-foreign-policy-the-challenges-in-the-mena-region/ [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- El-Gamaty, G. (2017). Qatar, the UAE and the Libya connection. com. Available at: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2017/06/qatar-uae-libya-connection-170612080219306.html [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- Kadhim, A. (2016). The Sunni conference at Grozny: Muslim intra-sectarian struggle for legitimacy. HuffPost. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/the-sunni-conference-at-grozny-muslim-intra-sectarian_us_57d2fa63e4b0f831f7071c1a [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- Khalaf, R. and Smith, A. (2013). Qatar bankrolls Syrian revolt with cash and arms. Financial Times. Available at: http://ig-legacy.ft.com/content/86e3f28e-be3a-11e2-bb35-00144feab7de#axzz4qZduUdS1 [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- Moubayed, S. (2017). How Qatar funded extremists in Syria. Gulf News. Available at: http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/qatar/how-qatar-funded-extremists-in-syria-1.2040774 [Accessed 1 Aug. 2017].

- Rabie, H. (1978). Political Relations Between the Safavids of Persia and the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria in the Early Sixteenth Century. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 15, pp.75-81.

- Reuters. (2011). Muqabalah – Islamiy Libiy Yutalib Al-Lajnah Al-Tanfiziyah Bi Al-Istiqalah. Available

Assalamualaikum warahmatullah

Perbezaan memahami nas atau fikiran tetap ada dan akan terus ujud, ia tidak memecah belahkan masyarakat selama semua pihak berada dalam batasan masing-masing sebagai contoh golongan syiah telah ujud dinegara kita seawal kurun ke 18, mereka telah menyumbang kepada pembangunan madyarakat Islam tetapi setelah revolusi Iran sebahagian angguta masyarakat Melayu berkiblat keQom dan mengutuk para ummahatul mukminin dan para sahabat maka ujudlah jurang kerana mereka merasakan lebih baik dan lebih benar, demikian juga dengan fahaman salafi yang giat berkembang kerana sebahagian yang terhutang budi dengan pemerintahan keluarga sa’ud telah menjadi “self appointed judges” menghukum sesiapa yang tidak sealiran sebagai sesat. Hal seperti juga pernah berlau seawal tahun enam puluhan apa yang dikenali kaum muda yang dipelopori Muhammdaiah tetapi tidak mendapat sambutan kerana asatizah menjadi benteng,

Kini keadaan semakin mencabar mujur Pergas-Muis memperkenalkan ARS.

Dalam penulisan diharapkan dapat menyentuh sedikit sejarah ini lebih adil dan melihat punca perbezaan.

Syukran

LikeLike